The Sociocultural Significance of salmon for tribes and First Nations

Summary of Findings

Photo: Chinook Salmon

Salmon are at the heart of the culture and well-being of hundreds of Indigenous communities in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Yet, declining Pacific salmon populations jeopardize the well-being of these Indigenous communities. At the same time, there is a lack of awareness about the scope, nature, and value of the Tribes’ and First Nations’ identities and practices that tie to Pacific salmon. Comprehensive understanding and appreciation of these multifaceted cultural relationships are critical for the social and ecological health of the entire region. This report lays a foundation to bridge those gaps, combining insights from one-on-one interviews, focus groups, community meetings, and publications on the sociocultural significance of salmon to Indigenous Peoples from Tribes and First Nations throughout the region.

The Pacific Salmon Commission (PSC), which is responsible for the implementation of the Pacific Salmon Treaty (PST) between the United States (U.S.) and Canada, is tasked with preventing overfishing and ensuring the equitable sharing of benefits from salmon originating from each country’s waters. To manage commercial, recreational, and subsistence fisheries in both countries, the PSC conducts research and convenes periodic meetings between national, provincial/state, First Nations, and U.S. Tribal delegates. The PSC contracted with Earth Economics to conduct this study on the food, social, and ceremonial (FSC) importance of Pacific salmon to Tribes and First Nations throughout the PST region. The project has been coordinated by the PSC Tribal and First Nations Caucuses.

The objective of this report is to convey Tribal and First Nations perspectives regarding the sociocultural significance of Pacific salmon. The goals of the project are to:

Provide a foundation to the PSC to understand relationships between Pacific salmon and Indigenous societies.

Raise awareness among Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities about the significance of Pacific salmon harvests and the importance of Pacific salmon conservation.

Provide information to support future funding and decision-making through the Pacific Salmon Treaty between the U.S. and Canada.

This webpage provides a summary of key report findings. For a copy of the Special Report visit the PSC website or download a pdf here.

Pacific salmon are a cultural and ecological keystone species, irreplaceable and core to the identities and ways of life of Indigenous communities throughout the Pacific Northwest. This page summarizes insights on the sociocultural significance of Pacific salmon learned from engagement with the Tribal and First Nations Caucuses to the Pacific Salmon Commission.

Framework

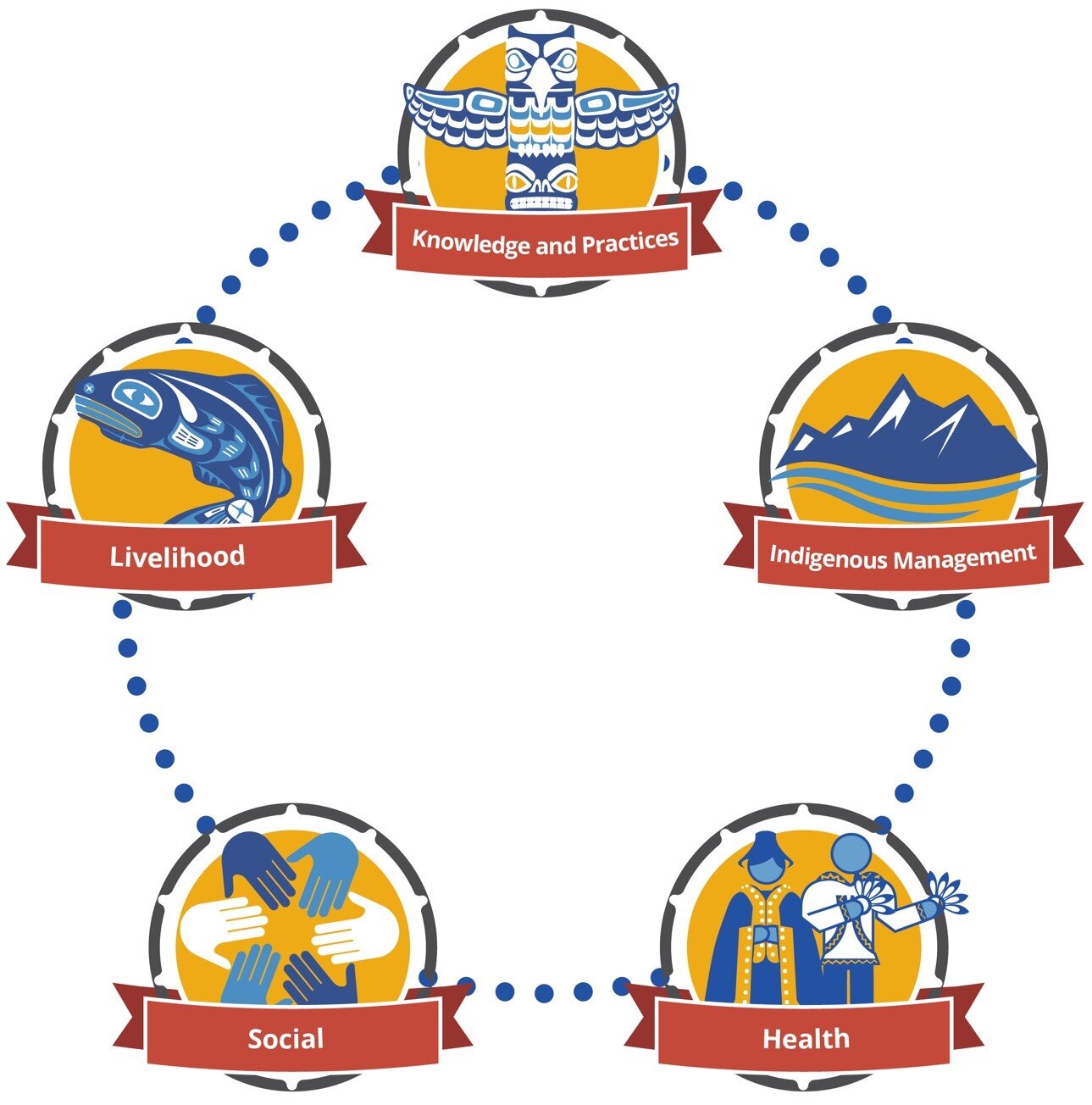

Centered around the well-being of Indigenous communities and salmon, our study organizes topics from interviews into a framework of five intersecting areas: social cohesion, health of humans and ecosystems, livelihoods, Indigenous management systems, and cultural knowledge and practices. A series of interviews shed light on the following themes that were commonly mentioned by project participants.

Salmon is a Social Fabric

Salmon are integral to family structures, community cohesion, gatherings and ceremonies, and practices of giving, trading, and sharing—all central to cultural identity. The breadth and depth of discussion around social gatherings highlight the ways families and Nations gather to cherish salmon. When salmon are scarce, Nations work hard to obtain salmon for ceremonial and subsistence needs in their communities and the communities of neighboring Nations. The exchange of salmon within and between communities strengthens the social fabric and cultural ties among Indigenous Nations.

Losses of Salmon and Cultural Wealth

Many salmon runs have declined significantly, and some salmon populations face extinction. Every participant in this study shared stories of impacts of salmon decline, including topics of food, habitat and ecology, going fishing, access to fishing areas, physical health, dams, and colonial governance. The loss of salmon is a cultural crisis: without salmon, ceremonies, food security, traditions, learning, economies, and health, all suffer. Indigenous communities feel a responsibility to stewardship that will ensure that salmon are available for future generations.

Healthy Salmon, Healthy Communities

Indigenous communities need salmon for their mental and physical health. Losses in Tribal and First Nations salmon fisheries leave communities without fresh, dried, canned, or frozen salmon, increasing their dependence on commercially processed foods. Discussions around food and livelihoods frequently stress the need for salmon for not only food and economic security, but also for sustaining human and ecosystem health, and teaching traditions and cultural practices.

Prioritizing Indigenous Management

Cultural needs, knowledge systems, traditions, and practices are central to Indigenous management approaches, yet these are rarely acknowledged, much less incorporated into agency management decisions. Displacement of Indigenous Nations from salmon and habitat management evokes feelings of sadness, frustration, and anger. This is especially true for Canadian First Nations. Despite legal precedents and government commitments and policies, recreational and commercial sectors are often given priority over Indigenous fisheries, further eroding trust. Effective conservation of salmon will require co-management and increased collaboration between harvest sectors.

Everything is Connected

Salmon are the lifeblood of Tribes and First Nations. Just as salmon are vital to ecosystem health and larger food webs, salmon are essential to every aspect of Indigenous livelihood and culture. The inability to fish salmon within traditional Indigenous territories breaks this cycle. Salmon are considered more than fish to be caught, eaten or sold, they are family members that must be treated with respect to ensure they will continue to provide to people and ecosystems. These values instill a responsibility for salmon: “if you take care of salmon, they will take care of you.”

Code intersections colored by domain. Thickness and color of lines represent more intersections. Codes with fewer than 10 intersections were excluded from this figure.

Recommendations

Shift priority from salmon harvests to rebuilding salmon populations, to ensure that Indigenous communities can meet their food, social, and ceremonial salmon needs now, and in the future.

Restore salmon ecosystems following holistic principles that draw on both Indigenous and Western science. This will require additional funding and support for Indigenous fisheries and fisheries science programs.

Respect and incorporate Indigenous sociocultural values, alongside Indigenous science and technology in salmon management. Indigenous Nations and Councils should be supported and consulted to enhance opportunities for cross-sector collaboration and Indigenous participation and representation.

Co-manage with Tribes and First Nations to fulfill Indigenous rights.

Considerations and Involvement

Special thanks to project participants, the Pacific Salmon Commission Tribal Caucus and First Nations Caucus, and Project Advisors: Murray Ned, Gord Sterritt, Russ Jones, Ron Allen, McCoy Oatman.

We would also like to recognize Talk To Type Transcription and the design work from Kauffman & Associates, Inc.

This project was funded by the Pacific Salmon Commission Southern Endowment Fund under the title Assessing the socioeconomics of food, social, and ceremonial salmon harvest and the grant ID SF-2020-I-16.

Land Acknowledgement

Earth Economics acknowledges that we operate on the lands of the Coast Salish people, specifically the ancestral homelands of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, and the 1854 Medicine Creek Treaty. Earth Economics intentionally strives to create inclusive and respectful partnerships that honor Indigenous Nations, cultures, histories, peoples, identities, and sociopolitical realities.